The Housing Development Board (HDB) has come a long way from its humble beginnings on 1 February 1960. Beginning with just a sprawling 21,000 flats within its first three years of inception, HDB has carried on the mission of providing affordable public housing to Singapore’s resident population, first set by the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT).

To date, 80% of Singapore residents have an HDB roof over their heads, with over 1 million flats spread across 24 towns and three estates.

Contents:

- The Singapore Improvement Trust – HDB’s predecessor

- When and why was HDB first established?

- How HDB flats have changed from the 1960s until today

- 1960s: Pioneer one- to -three-room flats

- 1970s: 20-storey point blocks and quality-of-life furnishings

- 1980s: Accelerating expansion with prefabrication technology

- 1990s: More variety and safety features

- 2000s: Greater demand for novel HDB developments

- 2010s and beyond: Mixed-developments for modern, convenient living

- Looking for a resale HDB flat?

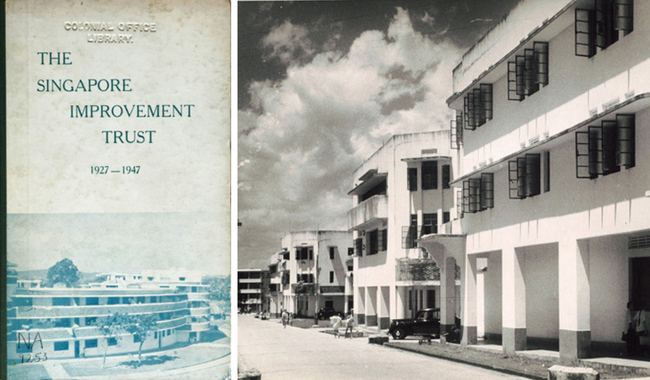

The Singapore Improvement Trust – HDB’s predecessor

HDB’s roots go all the way back to July 1927 when SIT was set up under the Singapore Improvement Ordinance to solve serious housing shortages amid a rapidly growing population. SIT’s initial duties were revolved around drawing up improvement plans, condemning unsanitary buildings, kickstarting development initiatives, and re-homing residents who were displaced by said initiatives.

As housing shortages persisted, the building of houses and flats for lower-income families was added to SIT’s scope. Just three years after SIT’s establishment, the Singapore Improvement Ordinance was amended in 1930 to allow for governor-approved buildings to be established “as the Board may think fit”.

The first houses built by SIT were lined along Lorong Limau in 1932. This was soon followed by their second-major project in Tiong Bahru, which became Singapore’s first-ever public housing estate. It comprised a total of 784 flats, 54 tenements (British-style apartments) and 33 shops.

SIT would introduce the Housing and Development Act 1959 (then known as The Housing and Development Bill) before eventually dissolving in 1960 when its respective divisions in master planning, planning and development were taken over by the Planning Department supervised by former Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew.

When and why was HDB first established?

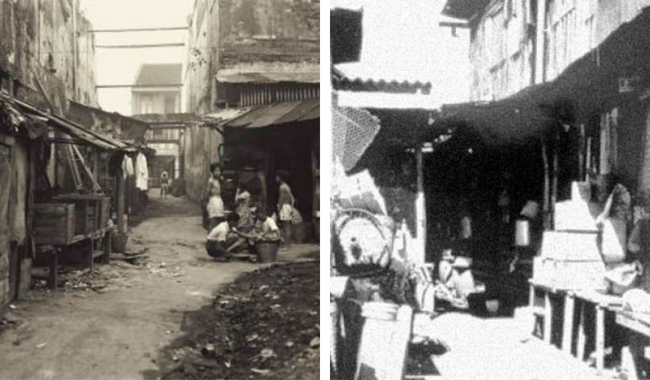

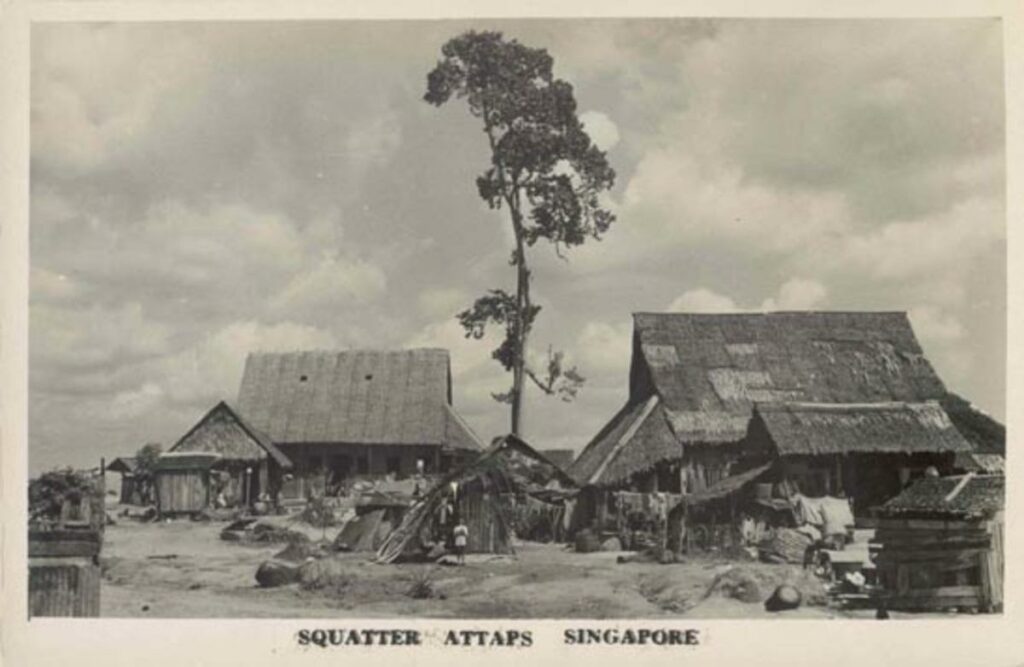

Despite the strides made by SIT, only 9% of Singapore’s population lived in government flats as of 1960. Over 250,000 people in central Singapore had to survive in overcrowded, unhygienic slums and squatter settlements. Conditions were so bad that more than 11 households or 83 people would squeeze into a single shophouse.

With the goal of eliminating a long-standing housing crisis in mind, HDB embarked on a five-year building programme that focused on the neighbourhoods of Queenstown, Bukit Ho Swee, Alexandra, MacPherson, St. Michael’s and Fort Road.

Their first order of business was to complete and refurbish the flats that they inherited from SIT. Three blocks of 7-storey flats on Stirling Road, Queenstown were quickly completed and residents began moving in in early 1961. Only three blocks — Blk 45, 48, and 49 — retained their original status as rental flats to elderly dwellers.

Shortly after, HDB planned and designed the town of Toa Payoh, the very first project that they were fully responsible for. The pace of development quickly picked up, with the number of flats more than doubling from 21,000 to 54,000 between 1963 and 1965. By the end of 1970, 36% of the population were living in HDB flats, with the present figure of 80% achieved just shy of two decades later in 1989.

How HDB flats have changed from the 1960s until today

1960s: Pioneer one- to -three-room flats

The pioneer batch of HDB flats were limited to one- to -three-room units aimed to resolve issues in squatter settlements, such as overcrowding, fire hazards, and an unhygienic environment. Their resolve to improve living conditions was only strengthened after the 1961 Bukit Ho Swee squatter settlement fire, which displaced about 16,000 residents living in haphazardly-erected huts primarily of wood and zinc.

In every new HDB unit, concrete blocks replaced wooden planks, flush toilets, showers and kitchens were connected to robust networks of water plumbing and electricity. In 1962, just one year after the Bukit Ho Swee fire, Block 8 Jalan Bukit Ho Swee was established.

Most HDB stacks in the 1960s were approximately 10-storeys tall, with about 12 homes on each floor. The units were linked by a common corridor, an enduring feature that can still be found in modern HDB flats throughout the country today. Units in these flats can be visited in Blocks 12, 13 and 14 on Merpati Road in MacPherson estate. They remain as the only standing two-room rental blocks in Singapore.

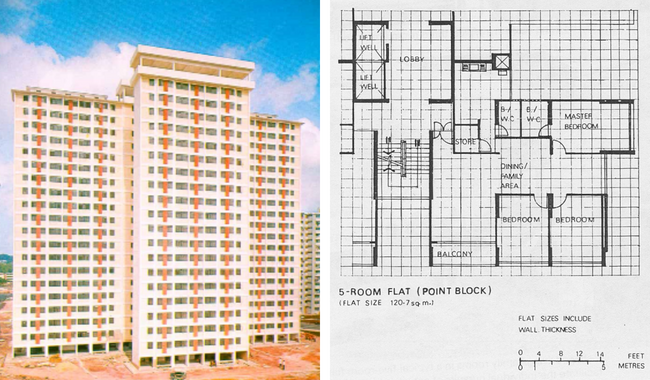

1970s: 20-storey point blocks and quality-of-life furnishings

The 1970s saw the introduction of 20-storey point blocks that towered over the pioneer HDB stacks. Point blocks were introduced to break the monotony of slab block designs and more closely resemble the HDB flats that we’re familiar with today.

As this was when HDB could afford to integrate quality-of-life features into residential buildings instead of just focusing on the bare essentials, the first point blocks featured just four units on each floor to maximise privacy. Units also became larger. Four- and -five-room flats, complete with toilet-attached master bedrooms, started mushrooming across HDB towns.

The years from 1971 to 1975 were also when HDB started its third, five-year building programme, shifting its focus to suburban areas like Whampoa and Kallang Basin. Swampy areas along the Kallang River were reclaimed for development, which explains Kallang Basin Neighbourhood‘s namesake.

Care was also put into ensuring that HDB flat surroundings were conducive for living and social interaction. This was when the now-iconic void decks were introduced, furnished with benches and chess tables to encourage social interaction between residents.

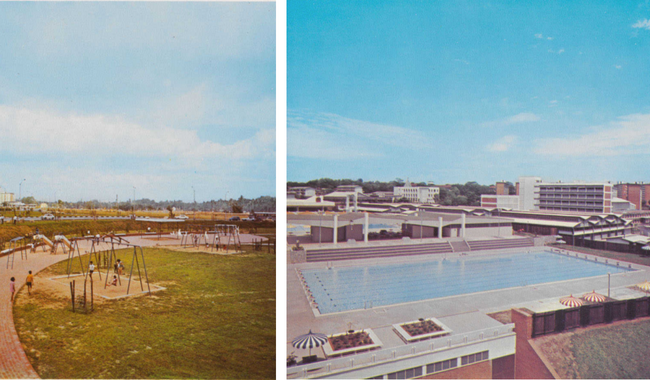

The concept of HDB towns with common facilities such as libraries, playgrounds, parks and swimming complexes were also introduced, with residents of Queenstown and Toa Payoh being the first to benefit from the projects.

1980s: Accelerating expansion with prefabrication technology

11 new towns had been constructed by the 1980s, but HDB was determined to accelerate development even further to provide housing for Singapore’s then population of 2.5 million.

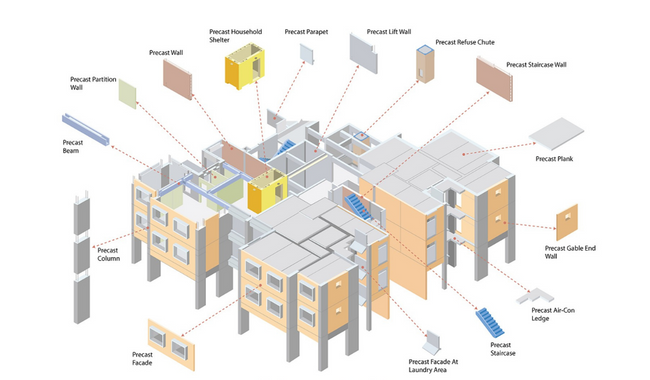

This was when HDB adopted prefabrication technology. Considered an innovative construction method at the time, prefabrication technology involved manufacturing building components off-site and assembling them on-site, less reliant on manual and unskilled labour.

The result was a safer working environment, better quality control, and a more efficient construction process. Prefab technology also reduced construction waste, noise and dust levels, and minimised inconveniences to residents living nearby.

Precast components continue to make up 70% of HDB buildings today.

The new-and-improved construction process gave rise to executive apartments, maisonettes (double-storey HDB units) and multi-generation flats. While maisonettes and multi-generation flats are no longer being built, this period saw HDB experiment with many designs to accommodate larger families while also giving character to HDB estates.

1990s: More variety and safety features

The 1990s were when HDB pulled out all the creative stops and began developing distinctive identities in each town. From unique street architecture to building designs, much care was taken into incorporating the heritage of landmarks on which HDB flats were built. To ensure that flats could be more accessible to the elderly and residents with mobility issues, lifts were designed to stop at every single floor.

1999 was also when HDB introduced subsidised executive condos (ECs) and premium apartments, complete with facilities you would typically find in a condo — swimming pools, gyms, and clubhouses.

ECs are technically hybrid public-private housing developments that are sold by private property developers: they are classified under the HDB public housing umbrella for the first ten years (from the date of its completion), which means that the usual regulations of the 5-year Minimum Occupation Period, HDB eligibility schemes, as well as resale levies applied to ECs as they would with average HDBs. By the 11th year, an EC would become privatised.

The 1990s also marked the tipping point when land constraints started to become an issue. As such, units built after the 1990s tend to be smaller than the ones built before.

The rise of terrorist insurgency groups in the region also prompted authorities to double down on public safeguards. Underground bomb shelters accessible from HDB void decks or basements were built to ensure that residents had a safe space to flee to in the event of a threat. These shelters were reinforced with concrete walls and blast-proof doors. Today, bomb shelters can be found inside HDB flats.

2000s: Greater demand for novel HDB developments

2001 would mark the inception of the Built-To-Order (BTO) system which has become synonymous with public housing — and even marriage proposals — in Singapore. Now an integral part of Singapore’s housing market, the BTO scheme allows potential buyers to ballot for a chance to select a new flat on sites that have not been developed.

Interested buyers would need to fork out a downpayment to “book” a BTO unit from any of the designated sites to keep out buyers who are only shopping around. Construction would only proceed if about 65% to 70% of the units have been booked. This way, HDB ensured that each one of their future projects would be filled with new residents soon after being built.

The pilot BTO scheme involved 2,500 new flats on four sites in Sengkang and Sembawang. By January 2002, BTO would completely replace its predecessor, the Registration for Flats System. Today, the BTO system is the main mode of sale of new flats.

As the general affluence of Singaporean households grew, more families began opting for private condos over HDBs. The Design, Build and Sell (DBSS) scheme was rolled out in 2005 to recruit the assistance of private developers so that unique, condo-like features could be integrated into HDB estates.

Meanwhile, one of the most iconic (and one of the most expensive) estates in this decade is undeniably The Pinnacle @ Duxton. The first release of 528 flats was oversubscribed many times over, receiving an overwhelming total of 3,149 applications. Today, the estate features 1,848 apartments in seven blocks, and is Singapore’s first ever 50-storey HDB project. The estate’s height allowed gardens to be featured at both the 26th and 50th level. Today, the rooftop skybridge continues to attract visits from the general public, who will get to enjoy panoramic city views for an entrance fee of $6.

The building’s height was so impressive that it continues to be HDB’s tallest project to date, and a watershed moment for the board’s push towards innovative, modern and green designs.

This period was also when Singapore’s first eco-precinct, Treelodge@Punggol, was launched. The precinct even features a living laboratory where sustainable technologies can be tested, signalling Singapore’s early preparation for the challenges of climate change that lay ahead.

2010s and beyond: Mixed-developments for modern, convenient living

With the foundation of sustainability laid out in the previous decade, this period would mark a time when HDB weaved more social, communal and environmental elements into its conceptual designs.

3Gen flats were introduced in 2013 to ensure that multi-generation families could have access to flats that are large enough to accommodate all their personal needs while also allowing them to live under the same roof. 3Gen flats typically feature four bedrooms, two of which have attached bathrooms, unlike regular flats which only have one master bedroom.

Applicants of 3Gen flats must provide evidence that their children and/or parents will be moving in with them, and cannot have any property registered to their name.

However, property experts have noted the lack of resale potential of 3Gen flats, as owners can only sell to other multi-generational families.

That said, they do fulfil a much-needed societal need. Working adults who double as their parents’ caretakers will be able to keep a closer watch on their parents while also having sufficient space to raise their children in these homes.

To further combat land constraints, HDB began awarding mixed-development sites to successful private developer bidders to allow for the integration of commercial and residential developments. Residents living in mixed-use developments can get to enjoy proximity to public facilities such as public transport, medical facilities, food courts and sports venues.

Mixed-use developments feature residential towers sitting on top of a commercial podium where businesses are allowed to move in to set up offices and store fronts. Reputable developers are known to entice anchor tenants and brands to ensure that the businesses within the commercial portion of the mixed-use development stays vibrant for the community.

Land beneath older landmarks and facilities are also being reclaimed and redeveloped to make way for fresh housing units that cater to needs of the modern family while still paying homage to the location’s past.

While the concept of HDB as an affordable and inclusive public housing option continues to be widely contested today, we’ve certainly made much progress from our squatter settlement days.

If you’re living in Singapore, expect to see a greater variety of housing developments (for example, the highly anticipated Tengah smart town) spring up in the next few years and even decades, as authorities and developers work together to transform the public housing landscape.

But here’s the thing: As homes have changed in the past few years, our way of selling them has changed too. Instead of going door to door in hopes of finding interested buyers and sellers, Ohmyhome has invested on hiring the best engineers, developers, and data analysts who are not just capable of building the best technology, but know the local property market as well as the back of their hands. And that’s how we find the perfect MATCH for our buyers and sellers.

Looking for a resale HDB flat?

Let Ohmyhome’s smart data-matching technology MATCH you with the right home, according to your specific needs. Submit your preferences to us and our algorithm will filter all our available listings based on those, and we’ll WhatsApp them to you once we find a match. We’ll also send you relevant content that you can use for your research and inform your home buying decision, so you no longer have to spend hours searching online for the information that you need. Because at Ohmyhome, we’re always by your side, always on your side.

You can also call us at 6886 9009 to secure an appointment with any of our Super Agents or message us in the chatbox at the bottom, right-hand corner of the screen. You can also WhatsApp us at 9755 9283!